Travel Tales Podcast

On Nov. 2-5, I had the pleasure of being a guest at Experience Bucharest– a four-day gathering of travel bloggers, influencers, journalists, etc. to promote the Romanian capitol as a tourist destination.

Having never been to Romania, I jumped at the chance. It also offered me an excuse to get the hell out of America for a bit – something I’ve very much looked forward to as of late.

No, I do not hate my country, but to escape the ugliness of the Nov. 6 midterm elections was sweet relief.

The rhetoric from all sides was more heated, ugly, and divisive than ever. Although had social media, 24-hour news networks and the like existed in Abe Lincoln’s day, I’m sure the online debates would have turned ugly pretty fast (Confederate Twitterbots, anyone?)

America, a young country by most world standards, is going through some growing pains.

Like a spoiled adolescent ignoring the sage advice of parents, America is throwing temper tantrums, having crazy mood swings, and hanging out with the wrong crowds. A lot of promise, opportunity, and potential is in danger of being wasted. And like that angry teenager, we also think a little too highly of ourselves and do way too many drugs.

To carry the analogy even further, our sullen teen country tends to fall asleep in history class and puts most of its energy into gym and recess. Someone once said “Those who ignore history are doomed to repeat it.” Or something like that… I can’t remember. I may have been playing dodgeball that day.

But Romania, like every region in Europe, has a history so long and varied that to not learn even a little something from its many incarnations would be like ignoring the canary in the coal mine: just because you don’t like the thought of dying, doesn’t mean you should ignore the gas leak.

Around the world, locals often chuckle at the sight of American tourists marveling at the age of things. Whether it’s a castle, a pyramid, or ancient works of art, we just can’t get over how old everything is: “You say this statue goes back to 300 B.C.?! Wow! Phyllis, did you hear that? B.C.!”

And that’s just it – we Westerners tend to forget just how truly young our civilizations are. Oh sure there were native people occupying our continents for thousands of years before European colonists arrived, but most of their history has been erased, re-written, or downright ignored by us conquerors.

You think the symbol for that iconic American institution of Disneyland was going to be a teepee? Fat chance – it’s a castle based on a real one in Bavaria.

The point is, Americans could do well with a few more history lessons. Which brings me back to Romania. Here is a region that in 2,000-plus years has been ruled by a number of foreign empires (Roman, Ottoman, Austria-Hungarian), not to mention ill-fated alliances with Nazi Germany and later, the Soviet Union. The locals have lived through tribal rule, monarchies (both local and from afar), communism, fascism, nationalism, dictatorship, and democracy.

Romania has endured revolutions, war, immigration, mass exodus, famine, disease, ethnic-cleansing, prosperity and poverty.

Today, gleaming glass office towers in Bucharest stand side-by-side with classic art deco buildings from the late 1800’s that still show bullet holes from the 1989 revolution. Romania has seen it all, it seems, and its resilience can serve as inspiration as well as a warning.

As my own country struggles to handle the very basic tenets of democracy these days (chaotic voting systems, denunciations of the free press etc.), I was ready for some lessons in resilience and perseverance. On the second day of scheduled tour options, I chose to continue my education with two tours: The Communism Tour and the Jewish Trail Tour.

Growing up in the 70’s and 80’s with the Cold War in full swing, Romania was synonymous with communism to me. That tour choice was a no-brainer. The other tour was a bit more personal.

In 1915 my Jewish, paternal great-grandfather boarded a steamship in Odessa, Ukraine (then Russia) just a few hundred miles east of Bucharest, en route to America for not only opportunity, but sheer survival. To stay in Europe as a Jew at that time was to face discrimination at the least, death at the worst. I never knew the full story of Romania’s place in all of it, and this seemed like the perfect opportunity to learn. What I didn’t expect was just how much more I related to it these days.

A week or so before my arrival in Romania, U.S. President Donald Trump declared in a speech that he was a proud nationalist. To the people of Europe and most other regions around the world, nationalism is something that sends up scarily familiar red flags (come to think of it, red is a popular color of a lot of those flags.) For them, nationalism evokes memories of the Dark Times of war and upheaval.

A particular dark subject was the story of Bucharest’s once-thriving Jewish community, as I learned on my tour led by a knowledgeable young man named Marius, of Jewish Trail Bucharest.

Marius, who was not Jewish himself but found the story interesting enough to devote much of his studies to the subject, walked us to the Jewish Quarter, and gave us the history of a once-thriving minority community that was a prominent part of the Bucharest daily life.

Jews had been well assimilated into the local fabric for hundreds of years, and many had even changed their surnames to blend in even more. But none of it mattered by the late 1930’s, with the advent of military rule, an alliance with Nazi Germany, and the emergence of the fearsome far-right Iron Guard militia.

While showing three of the seven remaining synagogues (two are now used as museums and cultural centers ), Marius told the story of the purge of the Jewish community.

There were tales of Iron Guard members storming synagogues and killing everyone inside before burning the structures to the ground. Concentration camps soon came, spelling the end for thousands upon thousands of not only Jews, but Rroma (formerly Gypsies), homosexuals, and nearly every other “impure” minority.

Fresh off the plane with a headful of American headlines, my mind drifted to the recent shooting of 11 people in a synagogue in Pittsburgh, and I nod knowingly.

Marius took us to a street where two buildings stood that had been designed by Jewish architects. One of the builders, he explained, was eventually forced to leave on an overcrowded ship filled with women and children that was turned away by other countries and sent out back out to sea with dwindling supplies and fuel. Eventually, the ship was sunk by a Russian torpedo.

I looked up to the sky and gave thanks to my great-grandfather, whose ship made it safely out of Odessa before he could suffer the same fate.

I thought of today’s refugees fleeing war-torn regions in Central and South America and the Middle East, only to be turned away, threatened and tear-gassed at the US border. “Build the Wall!” indeed.

But the tour was not all sad news. Yes, the Jewish community is a fraction of what it was before the war, but there is still a community, with the aforementioned temples and culture centers, a theater, and a Jewish school that remains one of the best in the city. Bucharest is a tolerant, typical European city these days.

Marius explained that he often leads tourists from Israel, many of whom are descendants of expat Romanians eager to learn of their family history.

It is a history of dark episodes for sure, but that doesn’t mean they should be ignored for being unpleasant.

On the contrary, with fascist politics on an upswing around the world, learning the lessons of the past is more timely than ever. Fueled by the financial crash of 2008, and intensified by the refugee wave from the Middle East and Africa, nationalist parties have been slowly adding more and more seats in multiple governments throughout Europe.

Far-right parties have made huge gains in Hungary, Austria, the Czech Republic, Switzerland, Denmark, Finland, Italy, and yes, even Germany has seen an upswing.

It was exuberant Romanian nationalism that helped solidify Nicolae Ceausescu’s power back in the 1968, when he publicly condemned the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia and sent a clear message to the Soviet Union that Romania had a mind of its own.

Ever since the end of WWII, Romania had lived under the Soviet shadow, and this push for independence made Ceausescu a popular man throughout the country. It wasn’t long before he exploited his popularity to seize total control- his motto was essentially a variation of “Make Romania Great Again.”

That last analogy came from our Communism Tour guide Elena of Open Doors Travel. When she referenced the Trump campaign slogan, the international crowd of bloggers gave a knowing chuckle. I, being the sole Yankee on the tour, felt less amused.

Starting with a brief history recap, fittingly on the steps of the National History Museum, Elena led our tour through Romania’s path toward communism.

For a region with such a long and varied history, the actual country of Romania is only 100 years old, formed in 1918 in the aftermath of WWI.

Before that, there was over two thousand years of smaller independent regions such as Transylvania, Wachovia, Bukovina, and Bessarabia functioning under various rulers, from both outside and within. Romans, Ottomans, Saxons, Austrians, Russians, Hungarians, all came through, as did Muslims, Christian Crusaders, Protestants, Jews and other religions.

“A land of immigrants,” I thought, “sounds familiar.”

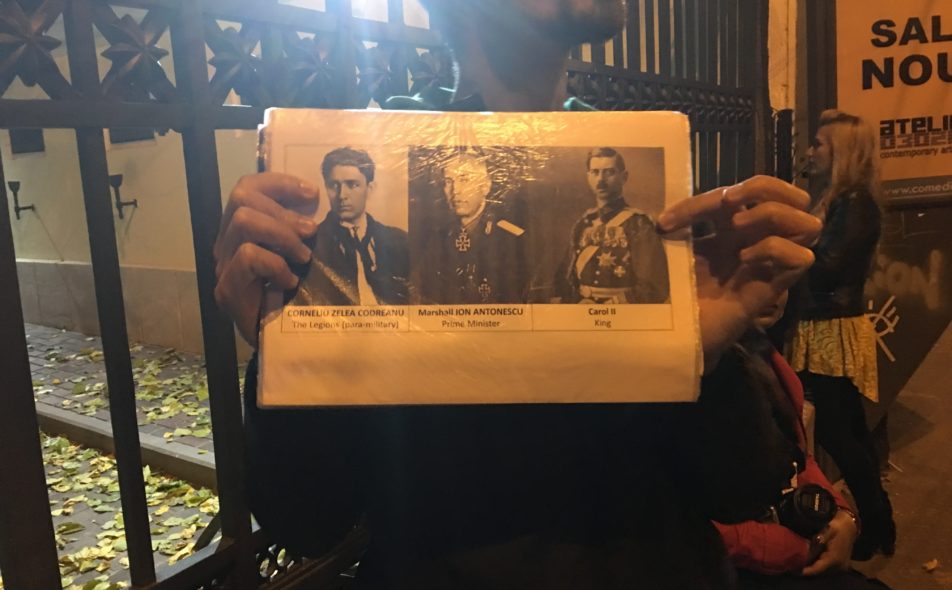

Between 1918-1939 was the era locals refer to as Romania Mare, or Great Romania. It possessed its largest land mass and had a constitutional monarchy under King Carol I. But, as we know all too well in the U.S., having a large, ethnically-diverse population can also stir up some nationalistic fervor against minorities.

Before long, a right-wing faction began to rear its ugly head with a mostly anti-immigrant, anti-semitic platform.

Combined with Hitler and Stalin having their own theories on what should be done with the region, Great Romania was not destined to last.

In 1937 right-wing parties, the Iron Guard among them, won around 15% of the vote, and a year later King Carol II (son of King Carol) tried to fend them off by establishing a dictatorship. But failed diplomacy led Romania to cede big chunks of its land. Off went Bessarabia to the Soviets (now Moldova); off went parts of Bukovina to Ukraine; here you go Hungary, you have a piece; and on it went.

Finally the army, led by Ion Antonescu, had enough, seized power, and aligned with the Nazis during WWII.

In August, 1944, the Soviets rolled their tanks into Romania and Antonescu was done.

There was a new sheriff in town, and his name was communism.

From 1948-1965, the leader of Romania was Gheorghe-Gheorghiu Dej, who finally convinced the Soviets to pull out its troops in 1958. When ol’ Gheorghe passed away in 1965, the reins went to his protege, Nicolae Ceausescu, whom he’d first met when the two were cellmates as political prisoners during the war.

Ceausescu was quick to consolidate his power. He became president of the State Council and declared Romania a socialist republic. At first, to Western eyes at the time, this didn’t seem like a such a bad thing.

In standing up to the USSR by not joining in the Czechoslovakia invasion, the West thought maybe Ceausescu was a guy they could work with. He became the first Warsaw Pact leader to welcome a sitting US President when Richard Nixon visited in 1971. The West cheered and so did the Romanians. Maybe Romania really could be Great Again.

But like a lot of people who get a taste of power, Ceausescu wanted more. This was when the story started hitting a tad close to my Trumpian home.

Inspired by 1971 visits to China and North Korea (North Korea, you say?), Ceausescu was blown away by the cults of personality created by leaders Mao Zedong and Kim Il-sung, respectively. He wanted some of that idol worship himself.

Having just watched my own newly-elected President glad-handing with Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong-un within his first months in office, I could only sigh.

Ceausescu came back from the Far East with new ideas: hold more military parades (that sounds familiar); crack down on journalists and the media (fake news anyone?); send thousands of political opponents to prisons (lock her up!); commission huge construction projects (construction? You mean, like a wall?); attack non-complying intellectuals (those damn cultural elites!); He banned abortion (hmmmm); and on it went.

By 1974, Ceausescu had become the de-facto head of state, but his big dreams came at a cost. Throughout the 70’s, the national debt exploded (you don’t say!), the poor got poorer (I hear that) and by the 1980’s austerity measures were put in place.

Food rationing began, and Elena showed us a list of the paltry amount of groceries each citizen was allowed each month. Without getting into too much detail, let’s just say it was enough for the typical American to consume in two or three lunches.

Before long, the hungry Romanian people were fed up with not getting fed up.

Ceausescu kept spending on massive construction projects like the giant housing blocs I had toured the previous day (what is it with these guys and tall buildings?) and the truly mind-boggling Palace of the Parliament, AKA the People’s Palace, the second-largest government building in the world after the Pentagon.

Costing an estimated $3 billion (US) to build, and under construction from 1984-1997, it was never truly finished. It now houses the new government offices and the Museum of Contemporary Art, but over half of it remains unused. Tours are available, but visitors only see around 5% of the complex. The locals don’t seem to promote the Palace tours as much, and considering what it cost them monetarily and spiritually, I’m not surprised when they don’t speak of it fondly.

Elena showed a photo of Ceausescu’s gold-plated Palace bathroom that caused outraged among the populace when it was discovered after the revolution.

To anyone who’s ever been in a Trump property or seen photos of his penthouse, Ceausescu’s boudoir barely elicits a shrug.

Speaking of the revolution, Elena walked us a few blocks north to the University Square, sights of many protests leading up to the December, 1989 riots. Then it was up a few blocks more to the now-named Revolution Square in front of the old Parliament building, where Ceausescu gave his final, fateful speech on Dec. 21 before escaping with his wife in a helicopter from the roof while demonstrators stormed the building.

We saw the rooftops where government forces turned their guns on protestors. In the end, 1,104 people died during the revolution, the final two being the Ceausescu’s themselves, executed by firing squad on Christmas Day.

As Elena explained, the execution of Ceausescu and his wife not only served to put an end to that particular period in the nation’s history, it also silenced the former dictator for good before he could name who had helped him along the way.

Many of those who served under Ceausescu not only walked away unpunished, but simply switched political parties and are still entrenched in government today.

Mysteries remain over who pulled the triggers and gave orders to kill citizens in the streets, and many in power would like to keep it that way. Nobody went to jail. “There is a political ruling class,” she said, “And they always seem to be the same people.”

“Meet the new boss,” I thought, “same as the old boss.”

I told Elena I had voted by mail in the US before leaving on my trip. She said that is impossible in Romania, as there is no voting by mail and no absentee ballots. Another arcane rule is that citizens can only physically vote in the town they are from. This adversely affects younger voters, many of whom have left their hometowns for work opportunities in cities or are living abroad.

As voter suppression tactics ramp up throughout the States, I will never take my absentee or mail-in ballot for granted ever again.

It is also said that history is written by the victors. This may also be the reason for the shockingly disparate states of the two monuments surrounding Revolution Square. The Monument of Rebirth, dedicated to the 1989 Revolution, is an abstract design that some say looks like a knitting needle skewering a rotting potato.

It is crumbling, graffiti-strewn, and seems to have been taken over as an ad-hoc skateboard park for wayward teens.

Elena said nowadays Romanian children learn little to nothing in school about the 1989 revolution, and therefore feel little obligation to respect its history. This is because many of those who worked alongside Ceausescu are still in power and would like to see this history erased. Judging by the state of the defaced monument, it’s working.

Meanwhile, just a hundred or so yards away, stands a statue of King Carol I, straddling his horse, staring boldly into the distance, the epitome of a strong leader- the embodiment of Romania Mare.

The monument is pristine, with nary a crack nor speck of graffiti. The children treat this statue with respect because this is the history they are taught.

It’s the history their leaders have chosen to teach, and why wouldn’t they choose that era? It is the history of victory and national pride: before the Iron Guard, the concentration camps, the Nazis, the Soviets, the secret police, the stifling of freedoms, and the food and fuel rations. This whitewashing seems to be having the desired effect:

According to recent polls, an increasing number of citizens actually long for the Ceausescu days, and if given the choice, would vote for him again.

History is a funny thing. As a child I was taught in school that Christopher Columbus was the hero who discovered America. The week I returned home to Los Angeles from Romania, city officials were permanently removing Columbus’ statue from Grand Park at the behest of Native American groups and others who now view him as the perpetrator of one of the world’s largest genocides.

Debate still rages in the American South about how to properly commemorate the tragedy of slavery, while standing under statues of Confederate generals.

How do educators in the US teach about Columbus now? What about slavery or Jim Crow? Do they teach that every US war was justified and we were always in the right? Which history do they pick and choose to share?

Studies show that more and more Americans believe the Holocaust was exaggerated, or even worse, believe it didn’t happen at all.

Who’s giving the facts, and who’s hiding them? What is fake news?

Those who have committed crimes and gotten away with it will do everything in their power to erase the past or rewrite history. Often their very lives depend on it. If that means rewriting the facts or burying them, so be it. If that means executing the old leader and his wife on Christmas Day, well it’s what needs to be done. And if it means burning books, denouncing the press, or arresting educators or anyone else who dares to preach an opposing narrative, then that time will come.

Americans often feel that somehow we’re different, that it can’t happen here.

As someone who’s been to over 90 countries and counting, my response is always, “Why can’t it happen here?” We are humans after all, and just as flawed as anyone. Our country is merely younger, that’s all.

America couldn’t even make it 100 years without having a bloody civil war that nearly ended the whole experiment.

Our borders have changed repeatedly – hell, there weren’t even 50 states until 1959. Our demographics have changed, our empire and alliances have changed – It’s all up for grabs.

Do I think America will always be a democracy? I’m not so sure. I’ve seen nothing around the world that guarantees anything.

I have had wonderful experiences traveling in Romania, Vietnam, Cambodia, Cuba, Japan, Hungary, Poland, and countries that made up the former nations of East Germany, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia – all of which were considered US enemies when my parents were growing up. In twenty years, our kids could be telling us Baghdad or Benghazi could be the hot new vacation spot.

Will I be shocked to find a heroic statue of Ceausescu in Bucharest if I return in 10 or 20 years? No more shocked than if I depart from Donald Trump International Airport.

We can’t merely learn the history that makes us feel good, or else we learn nothing. Time has a way of erasing the bad stuff. We prefer to remember the good times, when we were all younger, healthier, and full of hope. It inflates our self-esteem, but it also makes us think we were better than we actually were. Eventually the “Good Ol’ Days” become the “GREAT Ol’ Days” in our minds.

And then we get leaders who tell us they’ll make it Great Again.